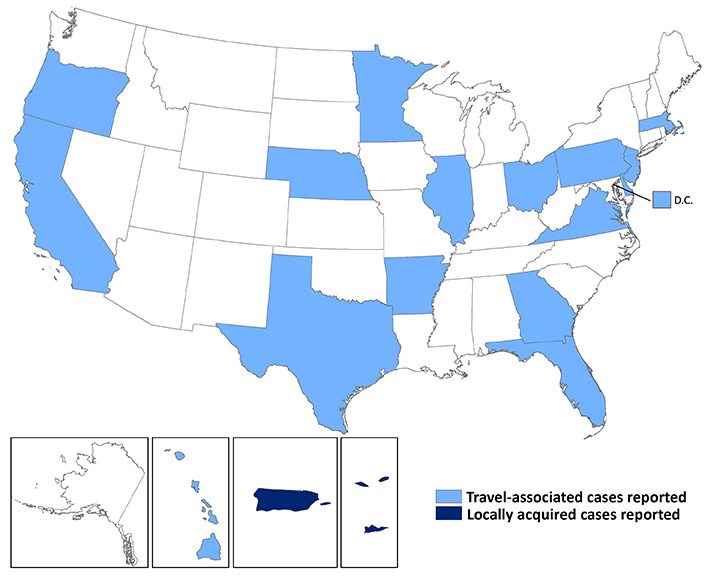

Zika virus disease in the United States, 2015–2016

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Map Last Updated February 10, 2016

On Thursday, February 11, Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro announced that at least three people had died due to complications related to the mosquito-borne Zika virus. These are the first Zika-related deaths in the South American country. Maduro also confirmed that 68 other people were in “intensive care” due to complications related to the virus. Since November 2015, Venezuela has recorded more than 5,000 suspected cases. The virus is spreading rapidly through South and Central America and is likely to result in some four million new cases this year.

At this stage, at least 20 countries have registered local transmission of the disease. Borne by theAedes mosquito, the disease produces no symptoms in the majority of cases and only mild symptoms such as fever, rash, severe headache and joint pain in other individuals. Despite this, the alarm surrounding Zika’s rapid spread through the Americas has reached fever-pitch in recent weeks as researchers draw correlations between infected mothers and infants born with microcephaly. Several studies are currently underway to conclusively determine the connection between the virus and microcephaly, but so far have been unsuccessful, showing only a strong causality.

In recent days suspicions have been raised by a group of Argentine physicians as to whether or not Brazil’s microcephaly crisis actually has Zika to blame. The World Health Organization (WHO) has been careful not to explicitly link Zika to microcephaly. WHO General Director Margaret Chan stated, “Although a causal link between Zika infection in pregnancy and microcephaly — and I must emphasize — has not been established, the circumstantial evidence is suggestive and extremely worrisome.”

The group of Argentine doctors suspects that, instead, a toxic chemical introduced into Brazil’s water supplies in 2014 to prevent the development of mosquito larvae in drinking water may be the real culprit. The larvicide, known as Pyriproxyfen, was used in a massive government-run program to control the mosquito population in the country. The group has pointed out that in previous Zika epidemics, microcephaly has never been linked to the disease. Further supporting their claim, the Columbian president has announced that, despite there being a widespread Zika outbreak in Colombia, there is not a single case of microcephaly there.

Meanwhile, the virus continues to spread. Russian authorities reported on Monday, February 15, that health officials have detected the country’s first case of the Zika virus in a patient who had recently visited the Dominican Republic. Russian citizens are medically tested upon return from countries affected by the Zika virus. Last week, Queensland’s Department of Health confirmed Australia’s third imported case of the Zika virus within a week, following two patients who contracted the virus in Samoa and El Salvador, respectively. It is also the first confirmed case of the virus in a pregnant woman in Australia. Health authorities in Australia have assured people that the reported cases do not pose a risk to those who have not recently traveled to a Zika-affected territory and that they would continue to enforce stringent monitoring at the country’s ports of entry.

In more encouraging news, the WHO has released a global Strategic Response Framework and Joint Operations Plan to help guide the international response to the frightening spread of Zika and the associated neonatal malformations and neurological conditions. The strategy will focus on “mobilizing and coordinating partners, experts and resources to help countries enhance surveillance of the Zika virus and disorders that could be linked to it, improve vector control, effectively communicate risks, guidance and protection measures, provide medical care to those affected and fast-track research and development of vaccines, diagnostics and therapeutics.”