Introduction.

Third-party delivery, in just a few short years, changed the face of the food and beverage industry as we’ve known it.

Ghost Kitchens are, simply put, cooking facilities producing food and beverages only for delivery or take out. There is no dine in option.

Pre-COVID, ghost kitchens were few and far between, created by enterprising F&B folks to capitalize on the growing market for food obtained by third party delivery. During the COVID-19 pandemic, however, ghost kitchens experienced a meteoric rise in popularity as thousands of restaurants were forced to (a) close entirely, (b) close their dining rooms and sell to go or by delivery only, or (c) see their dining room capacities limited to 25% 50% occupancy (as in Texas), while still being able to sell to go and by delivery.

Some existing restaurants simply created ghost kitchenesque elements within their existing operations in an effort to utilize existing space, expand offerings, keep people employed

The Pre-COVID State of Things.

Prior to March 2020, restaurants’ delivery sales we’re projected to outpace in store sales by more than three times through 2023. App-based third-party delivery platforms were encroaching on traditional, on-premise restaurant sales, forcing companies across all facets of the foodservice industry, from QSR to fine dining, to adapt to this new and growing trend.1

“As consumers find themselves more and more pressed for time, online orderingfrom restaurants has captivated a diner demographic increasingly shaped by the sophisticated world of consumer ecommerce,’ says Manny Picciola, Managing Director at L.E.K. Consulting and coauthor of Meals on Wheels: The Digital Ordering and Delivery Restaurant Revolution.‘ And millennials are a driving force behind the growth of digital ordering and delivery. We expect them to account for a full 70 percent of the at home delivery business by 2020.”2

Then COVID changed all that.

The Current State of Things

During the early pandemic months of March and April 2020, “thirty-three percent (33%) of customers reported that they were ordering more take-out.3

While the advent of ghost kitchens in recent, pre-pandemic years, largely involvedexperimental independents, chain restaurants have gotten into the game. As famously reported during the height (let’s hope) of the COVID-19 pandemic, a Philadelphia GrubHub customer sparked Internet outrage after learning that her order from Pasqually’s Pizza & Wings (which she thought was a local pizzeria), had originated at a Chuck E. Cheese’s restaurant.4 After finding her pizza was suspiciously familiar, a little internet research uncovered that:

not only was Pasqually P. Pieplate the name of the fictional chef in the Chuck E. Cheese universe, the Pasqually's "restaurant" had the same street address as Chuck E. Cheese. (And, making things worse—and more confusing—there’s a real West Philly pizza place called Pasqually's, one that has no affiliation with a giant cartoon rat.)5

Other chains are getting into the action, too, including Panera testing a ghost kitchen in Chicago, and “Denny’s [] adding two ‘virtual’ brands that won’t be on the dine-in menu, but will be made in Denny’s kitchens and delivered to customers.”6

As if war profiteering on the backs of the restaurant industry wasn’t enough, now the third party delivery services are getting into the ghost kitchen market. DoorDash Kitchens, opened in late 2019 in the San Francisco, CA, area, which provides customized kitchen space for five restaurant operations that offer delivery and pickup services through DoorDash’s app. The kitchens are separate, and the restaurants share storage and refrigeration space.7

The allure of utilizing space in this manner is clear:

Ghost Kitchens lack the typical infrastructure of servers, table service, and so on. Instead, this is a virtual restaurant restricted to mere takeout and delivery and restrained primarily by budget and imagination, and frequently a departure from a chef’s typical repertoire. It’s ideal for the low-touch COVID-19 age, when customers are leery of dining in but, perhaps, a captive and forgiving audience for experiments.8

But ghost kitchens still remain a viable option for independent restaurateurs, as well. In Dallas, Texas, acclaimed chef Nick Badovinus used his existing restaurants, their staffs, and their fully-equipped kitchens, to launch take-out/delivery-only concepts Vantina, Burrito Jamz ’03, Fajita Monster, Ese Pollo, Solid Gold Fried Chicken, and Pizza Parm Project. Unlike Chuck E., Badovinus marketed these concepts as “side hustles” from his parent company, FlavorHook.9 In addition to allowing him to employ his staff, the new offerings allowed Badovinus to serve his guests more fully, many of whom are either in high-risk categories for COVID, or simply skittish of going into restaurant dining rooms.

These ghost kitchens can allow restaurants to mak e up delivery costs on lack of overhead, and become a multi-meals-per-week dining destination for families.10

Concerns

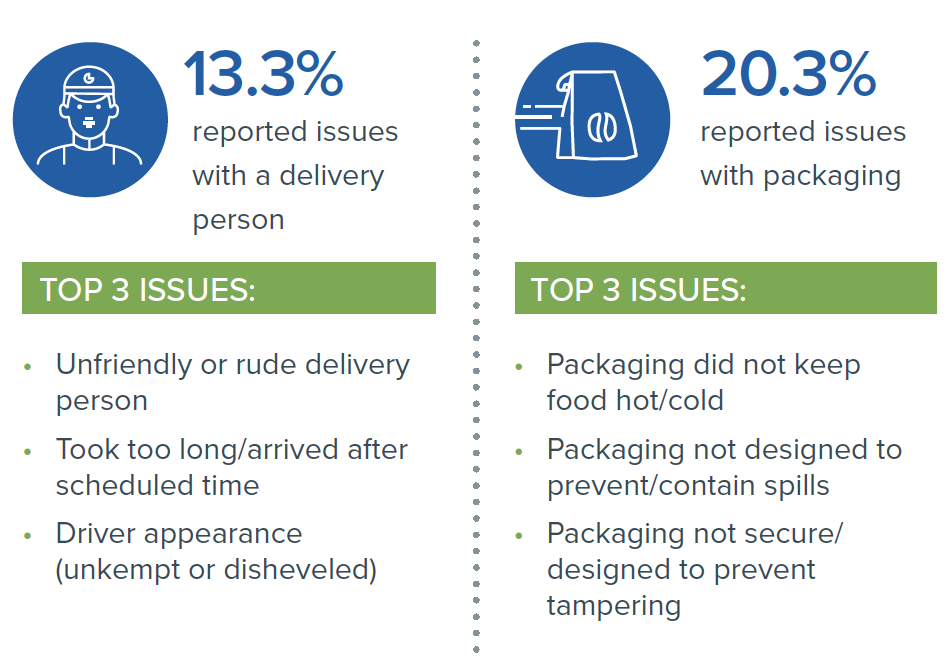

The rise of ghost kitchens, however, has not changed certain fundamental truths about third-party delivery. Restaurants must not only negotiate the pricing of delivery service, but should, perhaps over price concerns, prioritize negotiating the indemnity and liability shifting provisions in the services’ form contracts. Additionally, operators must take steps to protect their deliveries from tampering by delivery drivers,11 while ensuring their delivery packaging is adequate to maintain food integrity.

Other concerns to be addressed include delivery company insurance, disclaimers of agency between the delivery service (and its drivers) and the restaurant, compliance with safe food handling procedures, and mandatory driver tracking technology (so food integrity can be monitored, and foodborne illness claims can be refuted).12

The major hidden cost of third-party delivery(including thatdone from ghost kitchens), however, may appear in another realm altogether. Restaurants with leases requiring the payment of a percentage of gross sales (usually after a breakpoint of sales have been reached) may need to either renegotiate the definition of gross sales to eliminate the inclusion of third-party delivery charges, or negotiate with the delivery company to receive payment net of delivery fees.

For example, if the restaurant pays rent equal to six percent (6%) of gross sales, all sales are used to calculate that number, unless the definition of that term in the lease allows for deductions (usual deductions include sales tax and server gratuities, among others). When an operator makes $10,000 in sales in a month via third-party delivery, all $10,000 of revenue for those sales hits the restaurant’s point-of-sale system, and is consequently included in the gross sales calculation. The delivery service, however, will invoice the restaurant (usually weekly) for its share of the delivery sales (sometimes as high as thirty percent (30%), which the restaurant pays to the service. Thus, the restaurant faces the unenviable predicament of paying rent on $10,000 in sales, when it only realized $7,000 (making the effective rate of percentage rent much higher).

Ghost kitchens leasing space specifically for to go and delivery sales on a percentage rent

basis may be wise to exempt delivery fees from the calculation of gross sales. A restaurant adding a ghost kitchen concept to an existing restaurant location should examine its lease to determine whether such a move, of successful, could take it from base rent into a percentage rent situation, and if so, to specifically remove delivery fees from the calculation of gross sales when reaching out to the landlord to amend use and/or trade name information in the lease.

Finally, ghost kitchens must remain cognizant of not infringing on another’s trademark,

and should consider seeking federal trademark registration for their concepts, as if they were traditional restaurant names.

Conclusion.

As third-party delivery continues to grow in popularity among diners across all demographic groups, restaurants and other food and beverage operators must act now to negotiate contracts with those companies that offer competitive rates. They must also consider food safety and liability/indemnification issues, addressing issues that could affect a restaurant’s brand, and remaining vigilant in seeking to minimize the amount of rent paid on gross sales that include delivery revenue. Operators looking to enter the ghost kitchen game

1“Study: Delivery Sales to Outpace In Restaurant Sales”–QSR Magazine, March 5, 2019; available at https://www.qsrmagazine.com/news/study-delivery-sales-outpace-restaurant-sales (last visited Jan. 31, 2021).

2 Id.

3 Lalley, Heather; “How Will the COVID-19 Pandemic Crisis Change Consumer Dining Behavior?” Restaurant Business, April 10, 2020; available at https://www.restaurantbusinessonline.com/consumertrends/how-will-covid-19-crisis-change-consumer-dining-behavior (last visited Jan. 31, 2021).

4 Castrodale, Jessica; “Trying to Support a Local Pizzeria? Just Make Sure it isn’t Actually Chuck E. Cheese” Food & Wine, April 24, 2020; available at https://www.foodandwine.com/news/local-restaurant-on-delivery-app-actually-chuck-e-cheese-pasquallys (last visited Jan. 31, 2021).

5 Id.

6 Eaton, Dan; “Guy Fieri, Stouffer’s, and the surge of ghost kitchens in Columbus,” Columbus Business First, Jan. 30, 2021; available at https://www.bizjournals.com/columbus/news/2021/01/30/guy-fieri-stouffer-s-and-the-surge-of-columbus-gh.html (last visited Jan. 31, 2021).

7 Canales, Katie; “DoorDash is About to Start Trading on the NYSE. Here’s What it’s Like Inside its Silicon Valley Ghost Kitchen, a WeWork for Restaurants, that allows tenants like Chick Fil A to Focus on Delivery,” Business Insider, Dec. 9, 2020; available at https://www.businessinsider.com/doordash-ghost-kitchen-silicon-valley-chick-fil-a-photos-2019-11?op=1 (last visited Jan. 31, 2021)

8 Baskin, Kara; “Aberration or apparition? Ghost kitchens could replace your favorite haunt

,” Boston Globe, Jan. 26, 2021; available at https://www.bostonglobe.com/2021/01/26/lifestyle/aberration-or-apparition-ghost-kitchens-could-replace-your-favorite-haunt/ (last visited Jan. 31, 2021).

9 Ziots, Megan; “Nick Badovinus Adds Two More Restaurants to his Pandemic Friendly Pop Up Experiments,” Paper City, Sept. 17, 2020; available at https://www.papercitymag.com/restaurants/dallas-restaurants-chef-nick-badovinus-pop-ups-fajita-monster-solid-gold-fried-chicken/ (last visited Jan. 31, 2021).

10 See Baskin.

11 Matias, Dani; “1 in 4 Food Delivery Drivers Admit to Eating Your Food,”

NPR, July 30, 2019; available at https://www.npr.org/2019/07/30/746600105/1-in-4-food-delivery-drivers-admit-to-eating-your-food (last visited Jan. 31, 2021).

12 Orato, Damien and Singer, Suzanne; “The cost of convenience: Understanding the third-party delivery dilemma,” Nation’s Restaurant News, April 24, 2017, available at https://www.nrn.com/operations/cost-convenience-understanding-third-party-delivery-dilemma (last visited Jan. 31, 2021)

Leave a Reply